A trauma therapist's perspective on the cut’s IFS article

a hit piece is not trauma-informed

As Alana noted in supervision, The Cut’s recent article “The Truth about IFS, The Therapy That Can Break You” is far from trauma-informed. It’s alarmist, reductive, riddled with absolutes, and has enough clickbait to jolt us out of our politically-induced functional freeze state (just me?). The title claims a singular “truth” and the body touts a combination of biomedical hegemony, satanic panic, and sexually-laden legal scandals that are designed to elicit readers’ fears. And when the body is in a fear response, balanced critical thinking skills are compromised.

Trust the therapy community to process this article like it’s our job. It’s been a hot topic on listservs, whatsapp groups, podcasts, blogs, reddit threads, and our own internal meetings. What’s striking is the complexity of ethical questions it’s asking us to confront and the whack-a-mole nature of trying to define what the problem actually is. The article, despite its sensationalism, is prompting necessary conversations about IFS and the wider mental health industry under capitalism.

I’m not here to discredit the stories shared in the article or to wholeheartedly defend IFS. Most people close to me know I have issues with the IFS Institute and aspects of the model itself, which I may elaborate on further in a blog post – tbd. Still, countless people have been helped by IFS when practiced within the container of an intentional, trauma-informed therapeutic relationship built on trust and attunement. I intend to keep practicing it personally and professionally, so I want to share my take as a trauma therapist on the issues raised in the article and the conversations surrounding it, and explore what might help us ground.

a perfect storm

Any therapy modality, as with any medical intervention, can do harm if applied in the wrong context. Centering the client as a “person in environment”, we must ask: what does this particular person need, at this time, in this context, from whom, how, and why?

Residential treatment centers, no matter how bougie, provide insular care for a group of people with acute psychological distress, creating fragile conditions that bifurcate those in power (the management, staff, and clinical teams) from those in a vulnerable state (clients and their families). Interventions delivered in this setting deserve additional scrutiny.

The mental health industry, beneath any altruistic facades, operates within the realities of capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy. When left unchecked, power and profit come before collective good, and cis white men are disproportionately lauded for repackaging existing knowledge and practices into marketable therapeutic frameworks.

All of these factors created a perfect storm of damaging and unethical treatment at Castlewood. There were so many clinical mistakes. Blaming the IFS model and casting it as something that can “break you”, however, conflates correlation with causation and potentially discourages clients from seeking beneficial care.

If we zoom in, Castlewood, Mark Schwartz, and Dick Schwartz have to reckon with their own accountability and answer the questions: how did we let this happen and what can we do about it? (So far Dick and the institute have released this underwhelming response so jury’s out on that one.)

If we zoom out, mental health practitioners must examine how our own agendas (for profit, confirmation, expertise, authority) compromise client-centered care, how we involve clients in our therapeutic decision-making processes, and how we decide what counts as “effective” treatment.

where does the cosmos of my healing fit in?

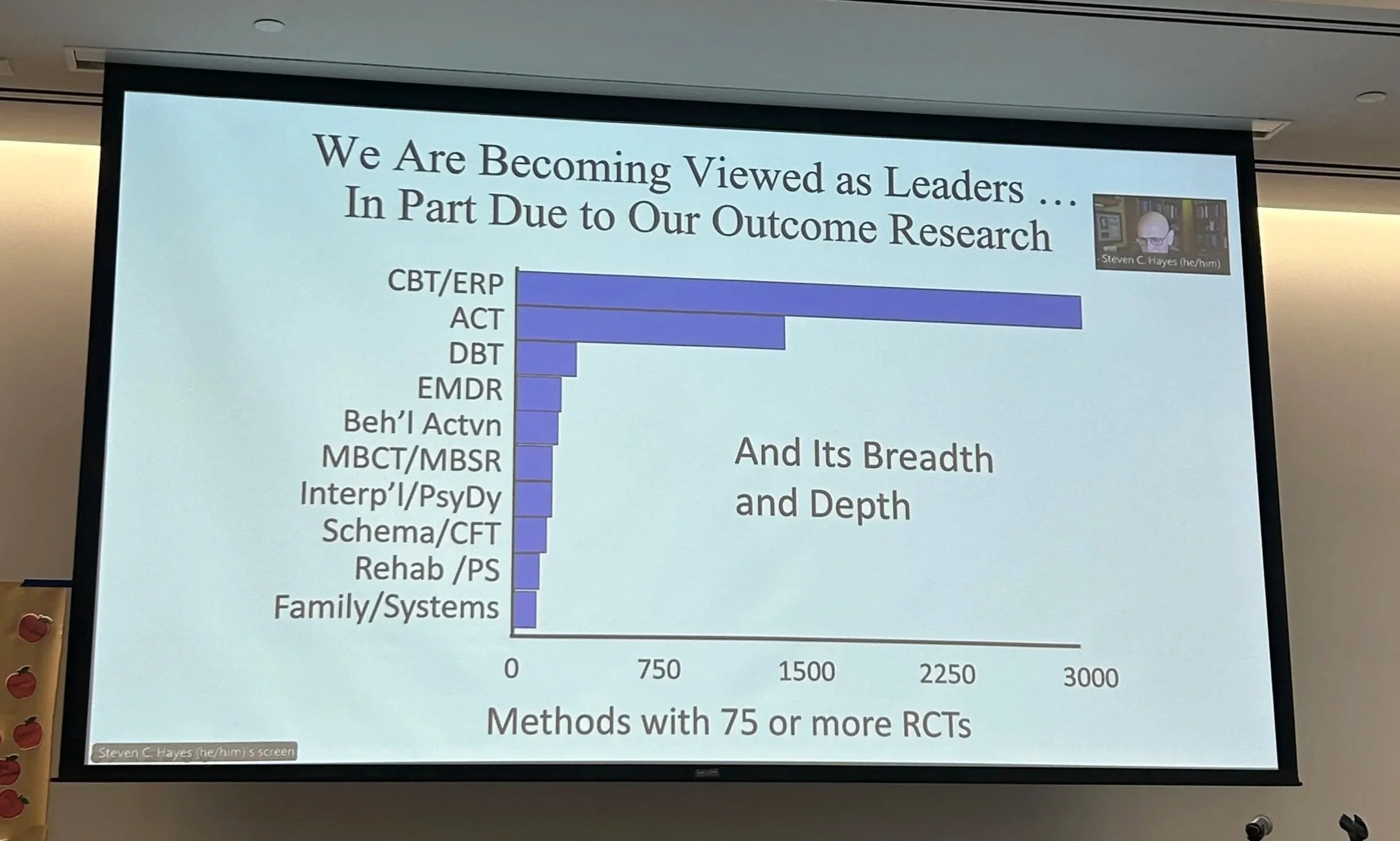

The mental health industry has pursued professionalization and legitimization by mimicking the medical industry with seeking “evidence-based treatment” via randomized control trials (RCTs), despite the unique challenges of mental health research (e.g. finding unbiased funding, adequately measuring the psyche within its social-cultural contexts, diagnostic ambiguity, reporting bias due to stigma, blinding difficulty…). Does this mean we should stop trying? No. There are still rigorous methods for measuring mental health outcomes and continued investment in mental health research is needed. It means we have to add extra layers of nuance to conversations about research and “evidence-based treatment”, which is a proxy conversation for what (and who) gets to define legitimate therapeutic practice.

Healing trauma requires left and right brain engagement. Sensory experiences, imagination, relational attunement, storytelling, cultural rituals, indigenous wisdom, creative meaning-making, and spirituality are all established tools for trauma recovery, but how do we measure these? Should we? Why or why not?

This is a slide from the recent NYC ACBS Conference Alana, Vineha, and I attended. The originator of ACT, Steven Hayes, spoke passionately (and a little chaotically, bless him) about both the importance of RCTs and their limitations, including studying mostly WEIRD populations and failing to capture the specific richness of the complex human we’re building a relationship with. As I scan the categorization of each modality, I wonder: where does the cosmos of my healing fit in? Where can I place Jenn, my first long-term therapist? Or Mr. Reddy, who taught me how to meditate? Or Kimm, who is 100% absolutely definitely from another portal and rocked my world with Havening?

too much, too fast, too soon

Alana’s comment had me thinking. A major problem with IFS is that its rise to popularity followed the contours of trauma itself: too much, too fast, too soon. Ironically for a model that’s built on the motto “slow is fast”, perhaps it grew rapidly without the systems and clarity to support it.

My process of applying for the official IFS Institute training in 2023 reflects this. At this time, the training was open to non-clinicians, which I genuinely have mixed feelings about (make it accessible + don’t gatekeep healing vs. add guardrails for who can safely deliver the modality - both valid). There was huge demand and short supply, creating a scarcity mindset that influenced my decision to dole out $4k as soon as I got off the waitlist (also, who can afford to do this while taking off 3 weeks of work for training? I struggled.). The training itself was messy but powerful. I learned an incredible amount about the modality, yes, but the real lessons were relational: discernment, boundaries, personal autonomy, self trust, honesty, and group dynamics. My skeptical parts kept me empowered, which helped me walk away with what I needed, including one of my best friendships.

not what, who

Maybe this is what the mental health field—and those who engage with it—needs on a larger scale. The science of therapy lives in the manual; the art of therapy lives in the relationship. We need both. The Cut piece exposes failures of relating—not only in the egregious harms of those it depicts, but in the sensationalized storytelling itself. It invites readers to distrust therapy, reinforcing it as the medical world’s underdog—stigmatized, misunderstood, and now even cheapened by AI. But when we buy into that cynicism, we risk losing sight of our own relational responsibility: to care about our clients and therapists as humans, to keep our individualistic agendas in check, to remember it’s not what, but who can help us heal.